FAQs

- Cornea: The clear, dome-shaped window of the front that focuses light into your eye

- Choroid: The layer of blood vessels and connective tissue between the retina and the white of the eye, also known as the sclera

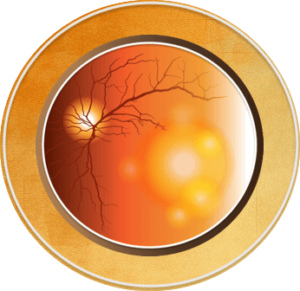

- Choroidal neovascularization: New, abnormal blood vessels grow in the choroid layer of the eye under the retina and macula that cause the area to swell, disrupting vision during advanced wet AMD

- Disciform scar: A scar that develops in the macula area of the retina due to fluid and bleeding from abnormal blood vessels in the eye

- Drusen: Yellow deposits under the retina that are made up of fats and proteins; drusen occur naturally with age and may be a sign of AMD

- Fovea: A small depression in the retina where vision sharpness is highest; the fovea is located within the center of the macula

- Fundus: The inside, back surface of the eye, which is made up of the retina, macula, optic disc, fovea, and blood vessels

- Iris: The colored part of your eye that controls the size of your pupil to let light into your eye

- Lens: A clear part of the eye behind the colored iris. It helps to focus light on the retina so you can see

- Macula: A small area in the center of the retina, which is responsible for straight-ahead (central) vision, most color vision, and the ability to see small details. This is the part of the eye that is affected in AMD

- Neovascularization: Growth of new (neo) blood vessels (vascularization) on abnormal tissue due to a lack of oxygen, occurs in advanced wet AMD

- Optic disc, or blind spot: The structure around the optic nerve where it enters the back of the eye (retina). It does not have light-sensing cells, so it is “blind”

- Pupil: The black part of your eye, an opening at the center of the iris that allows light to enter the eye

- Retina: The retina is the layer of cells lining the back wall inside the eye. This layer senses light and sends signals to the brain so you can see

- Sclera: The outer layer of the eye. This is the "white" of the eye

- Vitreous: A gel-like substance that fills the inside of the eyeball

AMD is characterized by complex changes in the eye, and what causes it is not completely understood. Age is a major risk factor for AMD; the disease is most likely to occur after age 60 years, but it can occur earlier.1 Other risk factors for AMD include people who: 4-7

- Are 60 years of age or older

- Smoking or history of smoking: Research shows that smoking doubles the risk of AMD; speak with your doctor if you would like help quitting

- Caucasian ethnicity

- Have high blood pressure or cardiovascular disease

- Eat a diet low in antioxidants or omega-3 fatty acids, or high in saturated fats and cholesterol

- A history of significant cumulative light exposure

- Are having a hard time seeing in dim light or the dark, or exhibit other AMD symptoms

- Have first-degree family members with AMD

Researchers have identified at least 20 genes that can affect the risk of developing AMD. Because AMD is influenced by so many genes, plus environmental factors, such as smoking and nutrition, no genetic tests can diagnose AMD or predict with certainty who will develop it. The American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) does not currently recommend routine genetic testing for AMD.1

An eye care specialist will perform a dilated eye examination using a slit lamp to assess the retina for drusen, changes to the retina, growth of abnormal blood vessels under the retina, fluid, or hemorrhage.5

The diagnosis of AMD is usually made clinically based on your history, symptoms, and confirmation with the dilated eye exam. However, other imaging tests can be used to gain a better understanding of AMD and to monitor progress before and after therapy.4,5

- Optical coherence tomography (OCT): An imaging technique that is not invasive and provides high-resolution, 3D, cross-sectional images of the retina; it can also help distinguish AMD from other retinal conditions

- Fluorescein angiography (FA): An Imaging technique that allows visualization of the blood circulation in the retina and blood vessels called the choroid using a special camera and dye injected into the arm; this test can also be useful in diagnosing other retinal disorders

- Slit lamp: A tool that combines a bright light with a microscope to examine the external and internal structures of the eye, including the optic nerve and retina

No FDA-approved treatment currently exists for early AMD. Everyone at risk for AMD should be educated about healthy lifestyle choices, including regular exercise, smoking cessation, wearing protective eyewear in the sun, and following a healthy diet that incorporates fruits, vegetables, fish, and nuts.1,4,8 Early recognition and coordinated care between primary care doctors and vision specialists may also help decrease the occurrence of permanent blindness due to AMD.5

Results from the Age-Related Eye Disease Study 1 and 2 (AREDS 1 and 2), two studies sponsored by the National Institutes of Health, show that certain nutritional supplements can reduce the risk of intermediate AMD getting worse.4,8 These nutrients include:

- Vitamin C

- Lutein

- Vitamin E

- Zeaxanthin

- Zinc

Based on the AREDS studies, people with intermediate AMD or advanced dry AMD, or vision loss in one eye due to AMD, should take AREDS nutritional supplements, which are available in different formulations for smokers and non-smokers.4,5

The first choice of therapy for persons with wet AMD is injections with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitors or anti-VEGFs. These drugs limit the destructive effects of abnormal new blood vessel growth on the retina and can stabilize or may reverse vision loss.4,5

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is typically used if there is no response to treatment with VEGF-inhibitors, and it can be used alone or in combination with VEGF-inhibitor medications. With photodynamic therapy, a dye that is sensitive to light is injected with an activating laser applied through the eye. Tissues with new vessels hold more dye than other vessels; when the dye is activated by the laser, it damages the abnormal, new blood vessels, making them stop growing.5

- An intravitreal injection is a way to deliver medication into the eye. A needle is inserted into the vitreous cavity in the middle of the eye12

- Usually performed in an office while reclined in a chair, the eye and eyelid are anesthetized using drops or gel, so the injection doesn’t hurt. The eye is cleaned, and an eyelid speculum is often used to hold the eyelid open. You will be asked to look in a particular direction depending on the location of the injection while the medicine is injected through the pars plana (the white part of the eye) with a very small needle12

- Typically, patients feel pressure, with little or no pain during the injection. After the injection, the speculum is removed, and the eye is cleaned. The entire process takes about 10 to 15 minutes12

Commonly performed as an outpatient procedure, a local anesthetic (by eye drop or needle) is used before you receive laser surgery so you don’t feel anything. A special lens is used to focus an intense beam of light on the abnormal blood vessels under the macula. By creating these small burns, the leaky blood vessels are sealed off, helping to prevent more vision loss.13 During photodynamic therapy, a dye is also injected to help to target the abnormal blood vessels.14

Some sample questions are listed below to help you begin the conversation with your clinician about your condition.

- Is there anything that be done to prevent worsening of AMD?

- What lifestyle changes might be helpful with AMD?

- What symptoms may I experience?

- Will I need treatment(s)?

- If I develop macular degeneration, will I lose my vision?

- If one eye is affected, will the other be automatically affected?

- How often should I see a specialist?

- Is it possible to get vision back after it’s been lost due to macular degeneration?

Use this tool for an easy symptom guide and questions to ask your primary care and eye care providers: AMD Checklist

Taking part in a clinical trial can be a great way to help improve treatment for your eye disease. A clinical trial can help both you and others who may benefit from the treatment if it is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in the future. Here are a few things to consider about participating in a clinical trial:

- Ask your eye doctor about clinical trials related to your eye disease.

- If your eye doctor says you may be a good candidate for a clinical trial, don’t be afraid to ask questions about the trial. Some possible questions: What would you need to do to participate? How many visits or appointments are needed for the trial? Is there any financial assistance with transportation costs for trial-related appointments?

- If you speak another language, find out if trial-related paperwork is available in your native language.

Before you join the trial, leaders of the clinical trial will let you know what you need to do to participate. They can also let you know how you can leave the trial if you choose to do so. Providing information about the trial and any potential treatment side effects is called informed consent.16,17

For more information about clinical trials, click here to access a variety of educational videos and information about medical research, as well as important questions to ask provided by the US Department of Health and Human Services.16 Sharing this information with your doctor can help you identify appropriate trials for your eye condition and support discussions on whether or not a clinical trial is right for you.

References

- The American Society of Retina Specialists. Age-Related Macular Degeneration – Patients. https://www.asrs.org/patients/retinal-diseases/2/age-related-macular-degeneration

- Eye Anatomy: Parts of the Eye and How We See. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Published April 29, 2023. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/anatomy/parts-of-eye

- Eye Condition Macular Degeneration Stock Illustration 83736805. Shutterstock. https://www.shutterstock.com/image-illustration/eye-condition-macular-degeneration-83736805

- Flaxel CJ, Adelman RA, Bailey ST, et al. Age-Related Macular Degeneration Preferred Practice Pattern®. Ophthalmology. 2020;127:P1-P65.

- Cunningham J. Recognizing age-related macular degeneration in primary care. JAAPA. 2017;30:18-22.

- Chuck RS, Dunn SP, Flaxel CJ, et al. Comprehensive Adult Medical Eye Evaluation Preferred Practice Pattern®. Ophthalmology. 2021;128:P1-P29.

- Cavallerano A, et al. American Optometric Association. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Care Of The Patient With Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Last reviewed 2004. https://www.aoa.org/AOA/Documents/Practice%20Management/Clinical%20Guidelines/Consensus-based%20guidelines/Care%20of%20the%20Patient%20with%20Age-Related%20Macular%20Degeneration.pdf

- About Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Vision and Eye Health. Published May 15, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/vision-health/about-eye-disorders/age-related-macular-degeneration.html

- Wet Age-related Macular Degeneration. https://www.macular.org/about-macular-degeneration/wet-macular-degeneration

- Practical Guidelines for the Treatment of AMD – Sponsored by MacuLogix – October 2017. https://www.reviewofoptometry.com/publications/ro1017-practical-guidelines-for-the-treatment-of-amd

- Dry Age-related Macular Degeneration. https://www.macular.org/about-macular-degeneration/dry-macular-degeneration

- Intravitreal Injections – Patients – The American Society of Retina Specialists. https://www.asrs.org/patients/retinal-diseases/33/intravitreal-injections

- Laser Photocoagulation for Age-Related Macular Degeneration. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/laser-photocoagulation-for-agerelated-macular-degeneration

- Raizada K, Naik M. Photodynamic Therapy for the Eye. StatPearls. Last update: August 8, 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560686/

- Woman with eye open in hospital under the microscope. iStock. Published January 11, 2016. https://www.istockphoto.com/photo/eye-surgery-exam-gm503559650-82600011

- HHS, Office for Human Research Protections. About Research Participation. Last reviewed May 10, 2023. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/education-and-outreach/about-research-participation/index.html

- FDA Office of Minority Health and Health Equity. Clinical Trial Diversity. Published online May 22, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/minority-health-and-health-equity/clinical-trial-diversity

- Macula Retina Vitreous Center. Photodynamic Therapy. https://macularetinavitreouscenter.com/services/surgeries-

procedures/photodynamic-therapy/

All URLS accessed October 1, 2024.